The event took place from April 4-6 at two sites – a house owned by the Sibley Family on El Paseo Ranch and Ironage Road, a 40 acre undeveloped parcel of land owned by HDTS. Together these spaces explored the tension between domestic and natural, human habitation and inhospitable environment.

The small house on El Paseo Ranch had drawings, photographs, sculptures, and performances ranging in subject from urban borders and suburban house facades to the housing market and building material. While the work here was innocuously subsumed by the domesticity of the space, the effect was important to the tensility between sites.

One of the projects that worked well in the first site was Carl Pomposelli’s “Almost Rhombus Studio Home.” Two shadow boxes were made out of the same drywall it encased, obliterating the division between frame and subject. It’s mundanity blended well in the bedroom space it hung inside because the quotidian context mirrored its own process. The drywall in “Almost Rhombus Studio Home” was first used in 2012 as a sculpture for Monte Vista Projects; thereafter, it was repurposed into pedestals and added to a wall with the intention of making a studio space into a more private homespace. Through multiple iterations, what remained of the material became autobiographical. A type of affective labor, the work discusses its own embedded conditions wherein studio/domestic and physical/psychological spaces blur into one another and the everyday proliferates. At Ironage Road, site-specific installation and performances were spaced out in an unassuming manner, giving precedent to the desert. The strong anchors at the site were works like Pomposelli’s that dealt with psychologically or physically negotiated home or art spaces, as well as those which observed the qualities of the desert and its role in American ideology and identity.

Near the road and hence near the “entrance” of the Ironage site was “The Icebox,” by Olga Koumoundouros. A vertical refrigerator door made out of wood board, on its surface was what appeared to be a collage of various flyers, papers, and drawings, some defaced, torn, or badly faded. This reference to ordinary objects displayed a disparaged perversion of the typical family refrigerator door. “The Icebox” uses “bondage as constriction and metaphor for economic and social precarity” in order to “depict the inherent sadism in our neo-capitalist system.” The displaced domestic good in the desert, while connoting middle class loss, also displayed a solidarity.

Also about loss, “Deep Cut,” by Marcos Rios was inspired by a series of prescient events in the artist’s life – the passing of his grandfather, his own brush with death, and the macabre subject matter at the gallery where he works. Additionally, Rios was tired of an old sculpture, “Rigor Motors,” which had been separated from its coffin counterpart; for the last ten years the sculpture had done little but collect dust and become a psychological burden. Ready to be rid of it, Marcos explains what solidified the idea of its burial: “During the week I was installing the death exhibition, Martin Scorsese’s Casino (1995) was playing on TV. I was listening to it in the background when I heard the line: ‘But it’s in the desert where lots of the town’s problems are solved…’Got a lot of holes in the desert and a lot of problems are buried in those holes.’ To mark the occasion, Rios put a grave marker that reads “Marco Rios, Rigor (Not Motors), 2004-2014.” Thus “Deep Cut” used the desert in a timeless application as a site to purge and create new beginning.

Not far from “Deep Cut” was Jay Lizo’s cardboard home, “Catan Firework House (L.A. Market 2001-2006)” which provided people with shelter and water. Inside the structure, the cool sand and the sun cast shadows filled the interior with kaleidoscopic colors reminiscent of stain-glass cathedrals. “Catan Firework House” is described by Lizo as a “darkroom or theater” whose form takes from the basic shape of a settlement in Settlers of Catan. The cut outs in the walls were a fusion of the pyrotechnic and the graph mark of housing sales between 2001 and 2005. Lizo has been interested in the inflation/deflation value of a house according to the perception of appraisers, homeowners, and neighborhoods. He states, “The goal of the piece was to immerse viewers in a room of spectacular color explosions of speculation and consumption.”

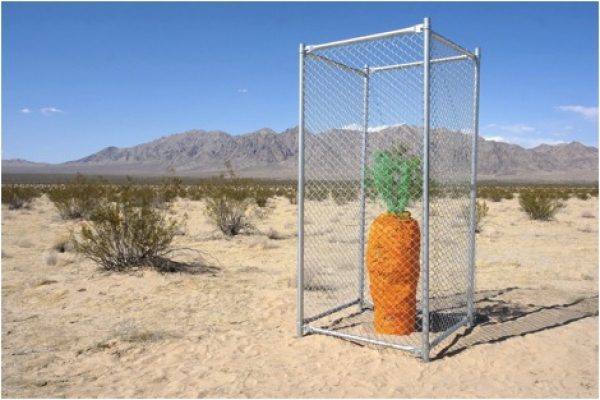

Some ways from Lizo’s impermanent house was a human size carrot half buried in the ground. It had a chain link fence (untied) around it, and brought to mind Mungo Thomson’s “The American Desert (for Chuck Jones),” an insightful study on the beautifully represented desert landscape in Looney Tunes. This piece by Matthew Usinowicz, titled “Left at Albuquerque,” was a humorous tribute to the surreal and cartoonish inspiration this barren place provokes, yet the carrot’s enclosure grounded it in the realities of property, territory, and human entitlement. Usinowicz discusses his inspiration for the piece: “I roamed the streets of Wonder Valley, 29 Palms, Desert-lands, California and became fascinated by the use of chain linked fence. What I saw were plots…surrounded by high fencing with intimidating barbed wire…Coming from San Francisco the idea of protecting land – especially in a place where there is plenty – is absurd. ‘Left at Albuquerque’ references Bugs Bunny on his way to Pismo Beach, where there are ‘all the clams you can eat!’ – an ideology most Americans share.”

Candice Lin’s “Grub/A Meal For Lizards” was an organic installation sensitive to the ecology of the desert and its indigenous animals. The artist placed vegetables and insects for lizards to consume in reptile-scale clay bowls and wooden table. Lin was interested in how shared meals could bridge species differences, in hospitality through nutriment, and in complications of home/security. Lin explains: “When I visited the site of the Iron Age Land and walked around the desolate landscape, I kept caving in the homes and tunnels of lizards and thought to myself, ‘Oh God, how inescapable that the idea of home involves the destruction of someone else’s home or security, or at least a kind of violence of taking-from-another when making oneself secure and safe.’…These kind of contradictions interest me – the hospitality and the violence within the idea of home…the body you are inhabiting, itself a kind of limiting home.”

The flux and insecurity of home seemed to be a common response in Spectacular Subdivision. Through High Desert Test Site’s base in Joshua Tree and 29 Palms, and Jay Lizo’s curatorial insight, Spectacular Subdivision brought together an eclectic group of artists and viewers who responded to the subject of housing in very personal ways. As Los Angeles and concentrated centers of cultural and capital production become less attainable to many Americans, peripheries such as the desert in neighboring San Bernardino county become migratory possibilities. All but one work in discussion here – burial and grave marker, a cardboard home, a large fenced carrot, a mock refrigerator door, drywall shadowbox, and a meal for lizards – remain in situ. The anonymity these objects assume post Spectacular Division mirrors the detritus traces of human activity that the desert (accepts) and reduces through disregard. It is the draw of this landscape, a place of seemingly unpollutable immensity, which offers an alternative perversion to the privileged and hierarchical spaces of capital we seek to escape from time to time.