A band of cowboys shooting at some unknown enemy. The Virgen de Guadalupe, hands clasped, head bowed, always watchful over her children. Soldiers raising the American flag at Iwo Jima. A pig smiling over a fence; unaware of its imminent end, and probable conversion into some delicacy to be enjoyed on a Sunday afternoon with family. The colorful, sometimes bright, sometimes muted, murals on San Bernardino commercial properties tell us the story of not only the business, but of the community in which they existed. More than an image on a facade advertising pupusas and Mexican food, they are stories of migration, hope, dreams, grief, and even loss. It is the story of America. And who better to tell these stories, than a poet and a photographer.

In an eclectic office, filled to the brim with books, paintings, and other tell-tale signs that an artist resides here (and that, really, could only belong to an English professor) I sat down to speak with photographer Thomas McGovern, and poet Juan Delgado about their new collaboration, Vital Signs; a book that forces us to pause and reflect on what we have been ignoring, and question what we have let go, and what we have to gain from bearing witness.

Isabel Quintero: I’ll start with the big questions. So, the title of the book is Vital Signs, which suggests life or looking for life. But a lot of the book, is about loss. How did you come up with the title?

Thomas McGovern: Technically, and this is sort of mundane, I already had the title for the body of work…But I think the bigger picture…would be that sort of vitality that all things [have]. Whether it be loss…experiencing loss is a very clear human experience and there’s a lot of vitality in it. So I think that sense of vitality would be in that sense of loss, or that sense of hope, would be one of those basic human emotions, with clearly a positive spin on it. We have a sort of optimistic point of view about it.

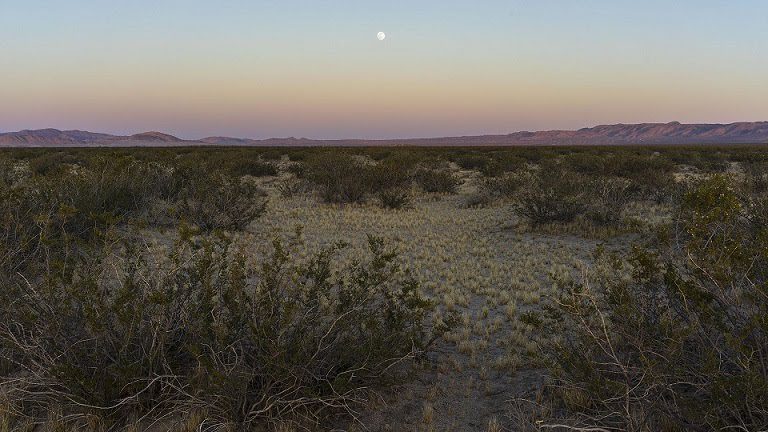

Juan Delgado: We did have a working title for the poetry, which the publisher, Malcolm, didn’t like, Lavish Weeds…About the lament or loss, we didn’t want to romanticize about [San Bernardino]–there was renewal, and there was hope, but there was also hardship. I don’t think there’s a paralyzing loss. There’s a sense of going through it. That’s one of the metaphors we see, in the paintings and murals being constantly redone, and reworked–but a lot of them are gone.

TM: And I think it’s a little corny to say it out loud but, without loss you really don’t know what you have. Just like anything in life…you don’t really appreciate anything until you have loss. You don’t appreciate how beautiful and precious life is, and it’s fleeting. Loss is a really important part of that experience.

IQ: Vital Signs is a document; you are documenting a lot things in here, and in your first poem, “A Point West of Mount San Bernardino,” you write “By the cameras/mounted on the street lights, you wonder/if they recorded the street sinking in the eyes/of the woman who died on a bus bench.” I thought that was interesting because you are reporting on something that is being documented by the city camera but nobody sees that; the camera is the only witness. But yet you’re writing a poem about it, and suddenly everyone gets to see it. Do you feel that your poetry gives voice to people, to citizens, who maybe don’t have a voice in the community of San Bernardino? That nobody sees? Except perhaps through the murals, or even through graffiti? Do you think your poetry does that?

JD: You know I guess, that’s a very interesting observation, and I’m very flattered. I think there’s a sense of the poetry that is witnessing…and I think part of the witness is seeing the kind of fragility and invisibility of some people, and that’s part of the story that Tom and I are interested in. Obviously we care for the city, and the city has people in it and the murals are represented by people’s efforts and lives…but when you see a fire and you see a whole neighborhood burn, you see just the squares of where the houses were. [Y]ou just see this perfect grid of devastation…which shows geographical order and structure, but in that is all decay and destruction. [I]t was a really difficult image to understand. You say, “Who are the mappers? Who’s charting this out? Who are the people behind all the symmetry and where are they at?” And so that’s another kind of witnessing; you have someone dying in the street, you have poverty. If you saw San Bernardino from a plane, you look down and you see these perfect squares and everything looks symmetrically beautiful. And the image shows control, it shows governance…and then you get into it and it shows something completely different. So witnessing that, and [asking] what does that mean, and how do we situate ourselves in that [is important].

TM: The thing about witnessing is that when you say that someone is a witness, they’re preserving what happened…that’s, I think, a beautiful thing that both the poetry and the photography are doing, too. We’re both pointing at something. Just as [Juan] slyly slips the camera image, being this cool detached observation, I sort of mimic in my photographs, but both poetry and the photography are telling you what was there, with that veneer of almost documentation or objectivity, which is nonsense because none of us are objective, but it does have that sort of sense that it’s preserving something, and of course both the poetry and photography is preserving what this place is about.

IQ: So in the past, Juan, you’ve done readings in furniture stores, and unorthodox places, not institutions. So it seems like there is a connection with the people, the community, not just poetry for us in schools–it’s poetry for everybody. And Tom, you’ve done photographs of wrestlers in their backyards, just everyday folk doing what they love. So how do you combine those ideas, or why do you do that? Why do you focus on that?

JD: There’s a lot of reasons I do that. When I think of galleries, or when I think of bookstores, or libraries, in a general way, they’re like cathedrals of culture…and [I] think this can be practiced outside the church…That’s what’s interesting to me, how you can define a space that you didn’t see as culturally interesting, like a furniture shop; that was one of my funnest readings. Just by going in there and doing a reading and changing the space, it could be used in so many ways…and I think Tom and I are interested in those [spaces]. Why do we have to segregate ourselves in these places that don’t include most of our community for the most part? And then you see some galleries that really try to bring aspects of our culture and diversity. We were at the Palm Springs Museum and Tom had the photography there, and for the first time we had a couple of Latino families there. There was a woman there who had her children, and she said, “You know, I’ve lived here…I saw Tom’s photographs and my culture was represented and I came to hear this talk.” Sometimes those places can be very inclusive, but it can be very isolating and cold and indifferent. So how do you break those barriers, instead of trying to recruit someone into that space, go to their spaces and do your thing.

IQ: Yeah. I think it often becomes an “us and them” issue, instead. You’re maybe taking photographs of the community but not as a part of the community.

TM: You know I think it’s one of those things, and any kind of art form always has this burden, there’s this popular notion that somehow art, anyone should be able to look at it and read it and understand it inherently, and it’s just not so. We have graduate degrees in these things. You know, people devote their lives to the study of poetry and art, and so necessarily it has a sort of elitism involved in it. It’s like, you show me a scientific equation, and I don’t know what the hell it means because I’m not trained in it. Of course it’s elitist. But, I think a part of what we both love to do with our work though is to take it out of the cathedral, and take it out in the street and see what it’s about…if you could make art about the everyday as opposed to a sort of more privileged experience, that someway makes it more profound. Certainly more powerful. When that lady came to that reading, and said, “I’ve never seen myself represented,” this is really what you want as an artist to have that experience, not just the experience of people who are already trained to have an experience.

JD: And we’ve had, at the art show opening [at the Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art], janitors come!

TM: It was so cool! Guys who’ve worked on campus for years and had never been in that museum before came that night.

JD: And they bought books and they bought books for their family members. We’ve had that experience in San Bernardino, where we had homeless people at our readings, and people who said, “Hey I know that place! I need to go get some keys made. Is that place still open?” I think that Tom has really put his artistic gaze in aspects of our city and has made it the stuff of art. And I hope to do that too, and it’s in keeping with, who are those people who did those murals, who did that signage, their artists too. In a way, we want to acknowledge that by where we do our thing. Sometimes those galleries and bookstores can be really closed communities where only poets are reading for poets. And so you think, that’s all cool, I have no problem with that, but at the exclusion for what? It’s really trying to find a balance in that. So it’s not like I really don’t do one or the other, but really find a balance. But going back to the question about witnessing is that I see myself as a public intellectual and I want to give back. Like Tom just said, we have gone to school, we’ve studied a lot, and many people have invested in us, so we have a lot of critical capital, like the ability to see photographs, create photographs, and write poetry. We want to take that capital back to the communities that helped us, that we came from, or that we want to be associated with. Do you follow me? It’s like we’ve been given something and we want to situate ourselves back in that community.

TM: And that’s where we come from too. We’re both products of public education, state universities, and both working class kids. The other thing that’s beautiful about what we’ve been doing, and I’ve been thinking a lot about it lately, is this idea of pride. And I’m not sure what the word pride even means, you know, I’m proud of this or that kind of thing. But we just worked with local kids here in San Bernardino…and just today I picked up some pictures from the students at [San Bernardino] Valley College who took pictures of their communities, and by naturally walking out the door and looking around and acknowledging where you live, for what it really is, without glossing it over, it engenders a sense of respect and out of that naturally comes a sense of pride about what this place is. And I hope that’s what [the] poetry and photographs do. Yeah, we get a lot of bad wrap, and we like to make fun of ourselves, but there’s so many beautiful experiences, and murals, clearly here and we want to just point at it and say, “This is a cool place too,” you don’t necessarily have to go someplace else.

IQ: What is the mission of this project?

JD: That’s a hard question. Tom and I have talked about this. We’re kind of like brothers in terms of how we see the world, and share convictions. My mom’s already adopted him as a neighborhood kid. You know I think [we’re] bringing our two types of artistic gaze to common things that we really enjoy and we’re working on…[and] re-appropriating the image of San Bernardino and identifying it; saying this is the stuff of art, and where we live is as beautiful as anywhere else.

TM: Yeah, I like to say that [Vital Signs] is a love letter to the city of San Bernardino, because we’re celebrating this place, even though there’s a lot of sorrow and loss mixed in both the pictures and the poetry, and personal experiences. But that’s the richness of the place. [P]art of the mission, at least for us, is what happens when we put these poems and these pictures together. We obviously had a firm belief that when you put them together this synergy happens, and the whole is greater…and we believe that it’s been more now through the experience of the book. If I were to tell anyone now that the quintessential experience of the book is to start on the cover and go page by page from the front to the back, reading every poem, reading every picture, and having one unified experience of it all at once, I believe that’s actually where it’s at its most beautiful and most profound, if I dare say. So, that’s kind of the mission. Of course we know the reality is that people flip through and look at pictures and read poetry however they want to. We’re not a dictator, we can’t force them. But that’s part of it.

IQ: How does this compare to previous work that you have done? Tom, with the AIDs book, and the wrestler book.

TM: For my photography, I’ve always had some sort of text involved, usually it’s the introduction. For the AIDs book it’s about people, so I had all these interviews. For the wrestling book it was the same way. You know, you think it’s about this silly subject, but when you read the interviews, you realize oh my God they’re very rich with peoples’ passions and dreams and loss, it’s really sad if you really read those. And so I think that notion that the text informs the pictures in such a deep powerful way, became really important to me. So this is another step…I’d guess I have to say my AIDs book is the richest, only because I know so many people who died but this is right up there with the kind of rich human experience, without having to stare in somebody’s face.

JD: You know, I have worked with another artist on another book…but what I really want to focus on that question is that working with Tom, going to the gallery, working with other artists, it’s really changed my sense that poetry has been somewhat limited. That sometimes poets are somewhat limited on how they think their words should be displayed, and how the staging of the words should be…Have I as a poet, really been limiting myself, by thinking of [poetry] as just a printed page, in a certain way? And it goes back to that idea of cathedrals that maybe shape us too much, to maybe think about how we stage ourselves or how we represent our work. This has been really eye opening in terms of collaboration and open…to all these really super rich experiences. Now I sit down and write and think, what’s the audio version of this? What’s the image version of this? You start thinking about all these other ways of thinking about the art.

IQ: Why is art important?

TM: Why is art important? Art is one of those funny things that you’re compelled to do. How am I not going to do this? Not only am I ambitious, but it’s like a drug that must feed some kind of dopamine in the brain. I mean, I’m tired right now, and I’m kind of burned out with school, and yet I’ve begun this whole other ambitious project with Juan that’s going to take a whole bunch of energy, and I’m dealing with people, and people are very messy, but I can’t help but do it. It’s like this drug that’s drawing you in and it’s of course feeding you. [E]ach time I make a new picture that I think is worthwhile, that huge charge comes back. I think a big part about art is our ego, of course about wanting to express ourselves, but the more you do it, the longer you’ve been doing it, it becomes like a life among itself, that’s dragging me along that’s pushing me along, and that I’m a collaborator with.

JD: A lot of people think that art is an escape from reality, from the real world. An alternative world; I don’t believe that. I think art helps us to more appreciate what we have…it helps us to sharpen our imagination, to look at our world with more interest, gaze, and wonder, and woe. And I think that art is a way to situate yourself in your world, not to escape it. So when you have to write about San Bernardino and say, “What do I love about this city?” It is a love poem; how do I express my love? Why do I love it? It’s not an escape from it but a way of going back into it. So I love how art allows us to go back into our world, and to appreciate it and see it.

You can purchase Vital Signs at Barnes and Noble, Costco, or online. The “Vital Signs” exhibition is currently up at the RAFFMA at Cal State San Bernardino, and will be up until July 31, 2014. For more information please visit http://raffma.csusb.edu/visit/exhibitions.html.